Prof. Dr Monika

Aggarwal Dean Chanakya Foundation,

Former Director,

National Institute of Fashion Technology

Introduction

The handloom and silk industries of Northeast India occupy a critical place in India’s craft heritage. Among them, Eri silk, or Ryndia, produced in Meghalaya, stands out as an ecological and cultural textile. While Assam is globally recognised for its golden Muga silk, Meghalaya’s Eri silk embodies an equally significant yet distinct identity. It is known for its soft wool-like texture, thermal properties, and ability to absorb natural dyes. Hand-spun and hand-woven Eri silk is both versatile and sustainable.

Produced from the cocoons of the Philosamia ricini silkworm, Eri silk takes its name from “erranda,” the Assamese word for castor plant, which serves as the main food for these worms. Unlike other silk varieties, Eri silk is obtained without harming the insect, earning it the alternative name “ahimsa silk.” It is the only silkworm species fully domesticated in India. The rearing and processing of Eri silk are chiefly handled by women from communities such as the Bodo, Mishing, Monpa, and Khasi in Assam, Arunachal Pradesh, and Meghalaya, where these silkworms are largely found.

For the Khasi, Jaintia, and Garo tribes of Meghalaya, Eri silk weaving is more than material production—it is a lived tradition, often associated with rites of passage, social ceremonies, and community identity. Women remain central to Eri silk weaving, reflecting gendered dimensions of craft traditions. Today, with increasing global emphasis on ethical textiles, Eri silk offers new pathways for cultural preservation and economic growth.

Textile historians and anthropologists have extensively documented India’s silk traditions, though Eri silk has often received less attention than mulberry or Muga. Research by Sen (2002) and Barooah (2011) highlights the ecological aspects of Eri cultivation, while more recent scholarship (Bhuyan, 2018; Khonglah, 2021) emphasises the cultural identity embedded in Khasi Ryndia. The Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO, 2020) has identified Eri silk as a sustainable material with global export potential.

Design studies (Das, 2019) point to the aesthetic particularities of Eri weaving, where motifs are largely geometric yet laden with symbolic meanings, often linked to tribal cosmologies. Textile economy surveys (Meghalaya State Sericulture Department, 2022) reveal increasing adoption of Eri silk in domestic and global markets, especially under the label of “peace silk.” This study expands upon three axes: (a) Eri silk’s production process and ecological features; (b) its design aesthetics and symbolic value; and (c) contemporary transformations in the face of sustainability-driven markets. It is based on Primary research, archival sources, and documented ethnographies of Meghalaya weaving communities.

The Production Process of Eri Silk

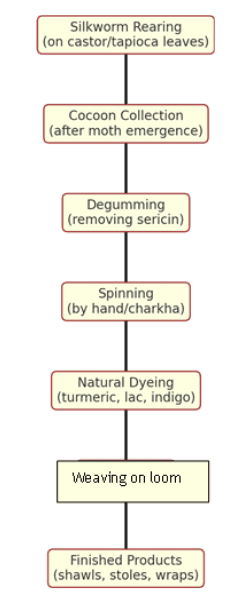

Sericulture and Cocoon Rearing:

Eri silkworms (Samia ricini) are reared on castor and tapioca leaves. The Khasi communities practice backyard sericulture, integrating silkworm cultivation into household economies. Unlike mulberry silkworms, Eri cocoons are open-ended, which naturally facilitates the extraction of silk without killing the pupae. This characteristic grants Eri its distinctive identity as “ahimsa silk.

The Eri silkworm is nurtured indoors and fed with castor leaves for about thirty days as it prepares for metamorphosis. Over the following fifteen days, it spins its cocoon, leaving a small opening for the adult moth to emerge and fly away. Unlike mulberry silk, the raw fibre from the Eri cocoon is not a single continuous strand but a cluster of short, interlaced filaments of varying thickness. This unique structure explains why the worms are not boiled during degumming and why the fibre is spun like wool rather than reeled.

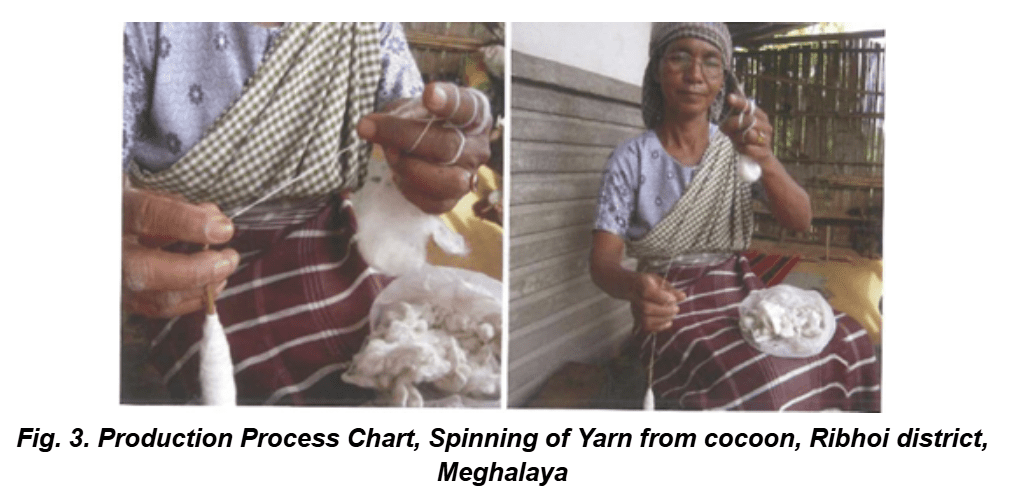

Each Eri cocoon produces a combined filament length of roughly 400 to 500 metres, about one-third that of mulberry silk. The outer layers of the cocoon contain the finest fibres, with a denier range of four to seven. Traditionally, the cocoons are wrapped in cotton cloth and boiled in water mixed with soda or plant ash to remove impurities. They are then opened, pressed flat into sheets, and joined together before being dried. Once dried, the fibres are spun into yarn using a hand spindle called a takli or, sometimes, a motorised spindle, making the Eri silk ready for weaving.

Cocoon Processing and Spinning

After moth emergence, cocoons are collected, boiled, and degummed to remove sericin. Unlike mulberry silk, Eri silk cannot be reeled. Instead, it is spun using traditional spindles or mechanised charkhas, producing a yarn with wool-like warmth and matte finish.

Dyeing Practices

Dyeing of Ryndia is traditionally done with organic sources:

- Turmeric (for golden yellow shades),

- Indigo (for deep blues),

- Lac (for reds and crimsons),

- Plant barks and roots (for earthy browns and blacks).

The eco-friendly dyeing methods are largely community-based, reinforcing the link between biodiversity and craft.

Traditional Natural Dye Sources for Eri Silk (Ryndia)

| Natural Dye Source | Local/Plant Name | Colour Obtained | Notes on Use |

| Turmeric | Curcuma longa | Yellow to golden | Widely used for festive shawls and stoles |

|

Indigo |

Indigofera tinctoria |

Blue (light to deep) | Often combined with turmeric for green shades |

| Lac | Resin from lac insect | Crimson red, pink | Used for borders and ceremonial wraps |

| Onion skins | Local vegetable waste | Light brown, tan | Sustainable household dye source |

| Natural Dye Source | Local/Plant Name | Colour Obtained | Notes on Use |

| Areca nut husk | Areca catechu | Rust, reddish brown | Common in Khasi traditional wear |

| Tea leaves | Camellia sinensis | Soft brown, beige | Produces earthy tones for everyday wraps |

| Plant barks/roots | Local wild plants (e.g., mangrove bark) | Dark brown, black | Used for grounding patterns and borders |

Natural Dye Sources, Shades, and Mordants for Eri Silk

| Dye Source | Shade on Eri Silk | Suitable Mordants | Effect on Fastness |

|

Turmeric (Curcuma longa) |

Yellow to golden |

Alum – bright yellow; Tannins – better binding; Iron – olive tones | Poor light fastness; moderate wash fastness with alum/tannin |

| Indigo (Indigofera tinctoria) |

Blue |

None (vat dye process) |

Naturally excellent light, wash, and rub fastness |

|

Lac (Kerria lacca insect resin) |

Crimson to pink |

Alum – bright pink;

Tin chloride – warmer red; Iron – purple/brown |

Good wash fastness; light fastness improved with iron |

|

Onion Skins (Allium cepa) |

Light yellow to tan |

Alum – bright tan; Iron – deep brown;

Copper sulphate – olive |

Good wash fastness, moderate light fastness |

| Areca Nut Husk (Areca catechu) | Rust to reddish brown | Alum – soft reddish tones; Iron – chocolate brown | Fair wash fastness, improved with iron |

|

Tea Leaves (Camellia sinensis) |

Beige to brown |

Alum – beige; Iron – dark brown;

Copper sulphate – olive-brown |

Excellent wash fastness; moderate light fastness |

| Dye Source | Shade on Eri Silk | Suitable Mordants | Effect on Fastness |

| Plant Barks/Roots (e.g., Terminalia, Acacia) | Dark brown to black | Tannins + Iron – deep black;

Alum – lighter brown |

Very high wash and rub fastness with tannin–iron system |

Natural Sources of Mordants for Eri Silk

| Mordant | Natural Source Examples | Notes on Effect |

| Alum | Naturally occurring alum stones (mineral deposits, e.g., from volcanic soils in Rajasthan, India); also extracted from bauxite-rich soils |

Gives bright, clear shades (yellow, red, pink) |

| (Potassium | ||

| Aluminium | ||

| Sulphate) | ||

| Enhances binding of | ||

| Myrobalan (Terminalia chebula) | dyes, improves wash | |

| Tannins | fruits, pomegranate rind, oak | fastness, often gives |

| galls, tara pods | yellowish or grey | |

| undertones | ||

| Iron (Ferrous | Rusted iron scraps soaked in | Darkens shades (yellow |

| Sulphate / | vinegar or jaggery solution | → olive, red → purple, |

| Ferrous | (“kasimi” in traditional Indian | brown → black); |

| Acetate) | dyeing); natural iron-rich muds | improves light fastness |

| Naturally present in malachite | Produces olive, teal, | |

| Copper | ores or derived from copper | and greenish tones; |

| Sulphate | utensils soaked with acidic plant | enhances wash |

| extracts | fastness | |

|

Tin (Stannous Chloride) |

Derived historically from cassiterite ore (tin oxide mineral) – less used today due to toxicity | Brightens reds and oranges (lac, cochineal) but not sustainable |

| Used to fix indigo vats, | ||

| Alkaline Mordants | Wood ash (potash lye), soda ash from plant ashes, lime (CaO) | adjust pH, and sometimes act as mordant in |

| yellow/brown dyes |

In traditional Meghalaya Eri silk dyeing, artisans often preferred eco-sourced mordants such as alum stone, myrobalan fruits, pomegranate rind, and iron-water (kasimi). These gave good fastness without relying heavily on industrial chemicals. The unique way of natural dyeing in Ri-Bhoi. Weavers of Ri-Bhoi use natural dye fixatives or mordants to improve or maintain colour when dying. For achieving better colour fastness properties, the Eri silk is often pre-mordanted before dying, and for achieving some shades, post-mordanting is also done. Some of the natural mordants are Sohkhu leaves (Baccaurea ramiflora Lour), Diengrnong, Tree bark, Sohtung leaves (Terminalia chebula Retz), Nuli leaves (Litsea Salisifolia), Waitlam Pyrthat leaves (Oroxylum Indicum) and Snep Sohmylleng (Tsuga canadensis).

Weaving Traditions

Weaving is done on the pit loom, operated mostly by women. The loom, while small, is highly adaptable and allows creative flexibility in patterning. Shawls, stoles, wraps, and blankets form the main repertoire. The slow rhythm of weaving embodies cultural patience and care.

Design Aesthetics and Cultural Symbolism

Khasi and Jaintia Traditions: The Khasi people associate Ryndia with ceremonial purity. It is worn during sacred festivals such as Ka Pom-Blang Nongkrem. Traditional motifs include stripes, checks, and small diamond patterns symbolising fertility, continuity, and connection to land.

Garo Weaving: In Garo culture, Eri silk is woven into warm wraps used in winter. Motifs are often geometric, but brighter natural dyes are used compared to Khasi weaving.

Motifs and Identity

Eri motifs are generally minimalistic compared to the highly ornate Muga and mulberry silks. The simplicity reflects tribal aesthetics that value balance, harmony, and symbolism over luxury.

Motifs and Symbolism in Eri Silk Weaving

The motifs and their symbolism in Eri silk weaving (Ryndia) are deeply rooted in Khasi, Garo, and other tribal traditions of Meghalaya, carrying both aesthetic and cultural meanings.

Geometric Motifs

- Diamond (Khnang, Khynriam, Pnar weavers): Represents fertility, the continuity of life, and cosmic balance. Symbolises protection, fertility, and continuity. Often seen in traditional wraps and stoles.

- Chevron & Zigzag: Symbolic of water flow, rivers, and movement, reflecting Meghalaya’s hilly terrain and monsoon-fed ecology. A metaphor for life’s ups and downs.

- Cross & X-patterns: Protective symbols warding off evil spirits; often woven into borders of shawls.

Floral and Botanical Motifs

- Lotus & Wild Flowers: Sacredness, purity, and harmony with nature.

- Areca Palm & Betel Leaf Patterns: Everyday cultural symbols tied to hospitality and social rituals. As sharing betel nut is integral to Khasi and Garo customs.

- Tree of Life: Found in wider Northeastern weaving traditions, symbolising prosperity and interconnection of the human–natural world.

Faunal Motifs

- Butterflies & Birds: Transformation, freedom, and spiritual journey; birds also connect the earthly and spiritual realms.

- Serpentine Forms: Symbol of rain, fertility, and ancestral powers in Khasi–Garo myths. Associated with water deities and protection in animistic traditions

Tribal Identity Motifs

- Clan Totems (e.g., animal or star-inspired shapes): Encode matrilineal clan identities and oral traditions. Specific motifs are linked to Khasi and Garo clans, functioning as markers of community identity.

- Star & Sun Patterns: Celestial motifs representing protection, enlightenment, and guidance in journeys.

- Protective Borders: Heavily patterned selvedge safeguards the wearer against evil spirits, reinforcing the textile as a protective layer.

Nature-Inspired Abstracts

- Sun, Moon, and Star Motifs

- Denote cyclical time, agricultural rhythm, and ancestral guidance.

- Raindrops or Cloud Patterns: Symbolise the fertility of the land and dependence on monsoons.

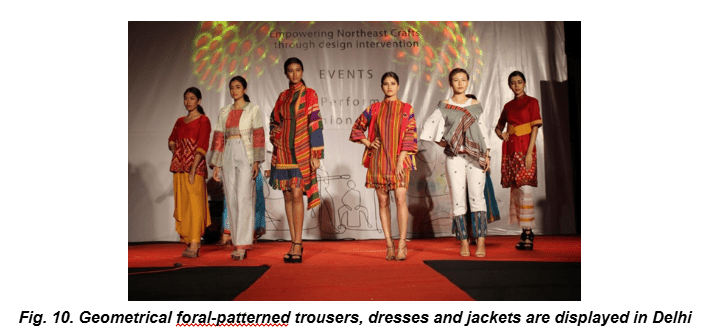

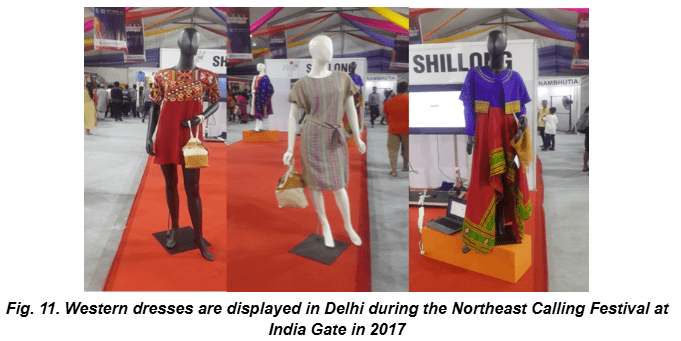

Contemporary Adaptations

- Modern Eri silk weavers incorporate minimalist geometric repeats (triangles, squares) and fusion floral patterns, blending traditional symbolism with market-driven aesthetics. These adaptations preserve heritage meaning while aligning with eco-fashion and sustainability narratives.

Cultural significance:

In Meghalaya, weaving motifs are not decorative alone — they carry coded meaning related to protection, fertility, spirituality, and identity. The Ryndia shawl, in particular, is often gifted at births, marriages, and spiritual ceremonies, with motifs chosen for their auspicious symbolism. Eri silk weaving is not just utilitarian but a living cultural text, where motifs encode belief systems, nature reverence, and social ties. Unlike mulberry silk’s luxury orientation, Eri motifs are more symbolic than ornamental, reinforcing sustainability, identity, and spirituality.

| Motif Type | Design Example | Symbolism / Meaning | Cultural Context |

|

Geometric |

Diamond, Chevron, Zigzag | Protection, fertility, continuity; Mountains and rivers (zigzag) | Common in Khasi wraps; abstract reflection of the environment |

| Floral / Plant | Lotus, Betel Leaf (Kwai) | Purity, spirituality (lotus); Social bonding, hospitality (betel) | Used in ceremonial shawls and gift textiles |

|

Faunal |

Butterfly, Bird, Serpent motifs | Transformation, freedom, protection, link to water deities | Symbolic of the spirit world in Khasi & Garo beliefs |

|

Celestial / Nature |

Sun, Moon, Stars, Raindrops, Clouds | Cyclical time, ancestral guidance, and fertility of land | Reflect agrarian rhythms, dependence on the monsoon |

| Tribal / Clan Identity | Clan-specific totems, Border patterns | Identity, protection from evil, continuity of lineage | Woven into borders and selvedge; inherited designs |

Eri Silk in Contemporary Contexts

Sustainability and Ethical Fashion

Eri silk is marketed globally as “peace silk,” aligning with sustainability narratives. Designers increasingly value it for:

- Non-violent silk extraction,

- Biodegradability,

- Compatibility with natural dyes,

- Soft texture suitable for winter fashion.

Economic Dimensions

The Meghalaya State Sericulture Department has expanded eri production through cooperatives and women’s self-help groups. Export demand has grown in Europe and Japan, where ethical fashion markets thrive.

Comparative Analysis of Mulberry, Muga, and Eri Silk

| Silk Type | Texture | Production Process | Cultural Role |

| Mulberry Silk | Smooth, lustrous, fine; soft drape | Reeled from

continuous cocoons; pupae are killed |

Widely used in sarees and luxury fashion textiles |

|

Muga Silk |

Golden-yellow sheen; durable, glossy, rare | Exclusive to Assam; reared on Som & Soalu leaves; cocoons boiled for reeling | Reserved for Assamese royalty and rituals; GI- tagged heritage textile |

|

Eri Silk (Ryndia) |

Matte, wool-like, warm, soft but not shiny | Spun from open-ended cocoons after moth emergence (non-violent) | Symbol of purity in Meghalaya; central to Khasi, Garo, and Jaintia identity |

Innovation and Globalisation

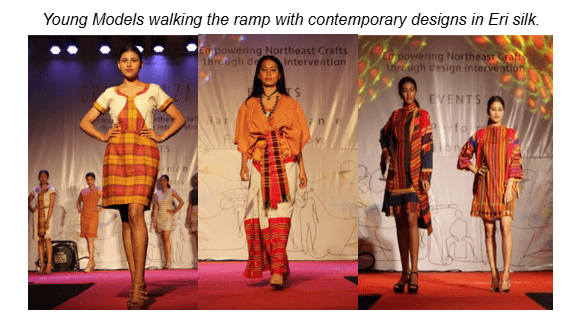

Experimentation includes blends with cotton and wool, digital printing, and eco-fashion runway showcases Shillong campus students. Eri silk illustrates how craft practices can align ecological sustainability with cultural heritage. While mulberry and Muga silks often symbolise luxury, Eri carries the ethos of ethical living. However, challenges remain: limited mechanisation, rural poverty, and declining youth interest in weaving. To sustain the craft, policy support, design interventions, and global market linkages are crucial.

Conclusion

Meghalaya’s Eri silk exemplifies how a craft can embody ecology, economy, and identity simultaneously. Its production process is a sustainable alternative to industrial silk, its design traditions preserve tribal worldviews, and its future in ethical fashion aligns with global sustainability goals. Strengthening this heritage through institutional support, design innovation, and fair-trade networks will ensure that Ryndia continues to be both a cultural treasure and a fabric of the future.

References

- Sen, S. (2002). Silk Traditions of India. New Delhi: Ministry of Textiles.

- Barooah, P. (2011). “Sericulture and Rural Livelihoods in Northeast India.” Journal of Rural Development, 30(3), 327–340.

- Bhuyan, J. (2018). Eri Silk: The Fabric of Peace. Guwahati: Assam Silk Board.

- Khonglah, M. (2021). “Ryndia: Khasi Weaving Traditions and Contemporary Transformations.” Indian Journal of Textile Studies, 12(2), 45–59.

- Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO). (2020). Sustainable Sericulture: Global Case Studies. Rome: FAO.

- Das, T. (2019). “Design Narratives of Eri Silk in Northeast India.” Craft Studies Quarterly, 5(1), 67–82.

- Meghalaya State Sericulture Department. (2022). Annual Report on Sericulture and Weaving. Shillong: Government of Meghalaya.